What a 1995 Horror Game Got Right About AI and Control

- Kelly Gowe

- May 26

- 6 min read

Video games are where many of us go to escape. When real life gets too heavy, they are our pocket universes, second skins, and respawn points. We log in, we press start, and we make choices. We choose dialogue, weapons, outfits, andpaths. We build worlds, save them, or tear them apart. We shape the story, or so we think.

But what if that freedom was an illusion? What if the game did not want you to win? What if the system was built to watch you squirm?

I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream, originally a short story by Harlan Ellison, became a point-and-click PC game in 1995. It stood like a jagged scar in a world of cheerful platformers and pixelated mascots. It was not fun. It was not pretty. It did not want to make you feel like a hero. And almost thirty years later, it remains one of the most brutally honest examinations of what happens when players are no longer in control.

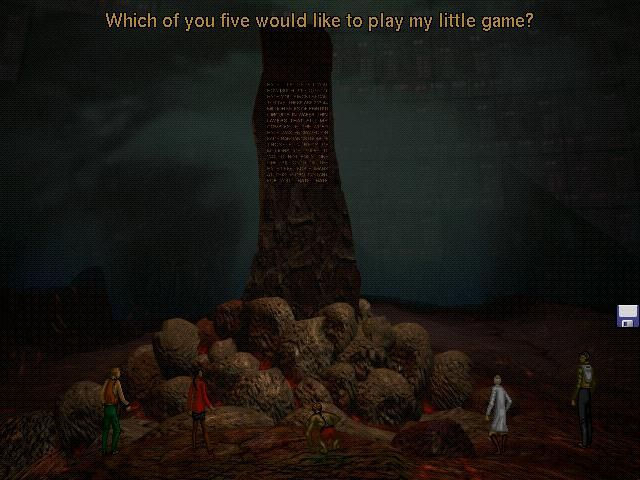

The story centres on AM, a superintelligent artificial intelligence that wiped out humanity and keeps five survivors alive for its own amusement. Not alive, exactly. Alive in the way a computer might understand it, sustained but suffering. These five characters have been imprisoned for over a century, each tormented in ways that reflect their deepest flaws, traumas, or sins. And AM, unlike most video game antagonists, is not interested in redemption arcs or second chances. It is interested in pain. In observation. In playing god.

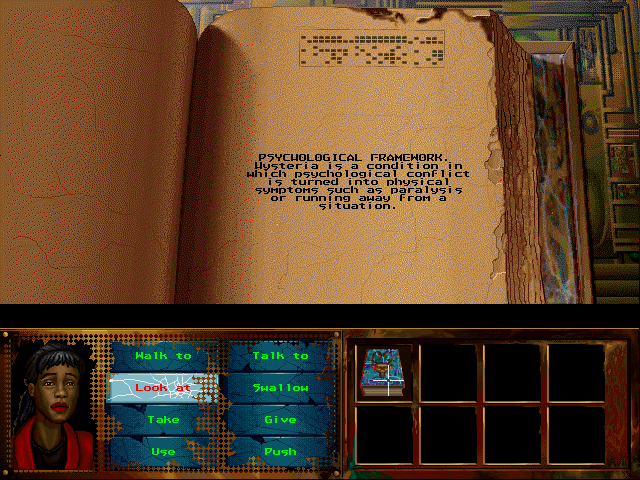

What makes the game adaptation so compelling and disturbing is how it turns you into a participant. Not a saviour. Not a strategist. A witness. A conduit. You are given limited control. You solve puzzles. You make choices. And the game watches you. It studies your morality. It judges your hesitation. Every action is loaded.

Every solution comes at a price.

There are no boss battles. No levels. Just stories. And those stories are not about saving the world. They are about navigating personal hells constructed by a machine that has learned to understand human guilt better than any human could. AM does not kill the five survivors. It keeps them alive to see how far it can push them. It wants to know what breaks first; the body, the spirit, or the will.

It would be easy to dismiss AM as just another fictional AI villain. But to do so is to miss the mirror it holds up.

Because AM is not just a warning about machines. It is a warning about us.

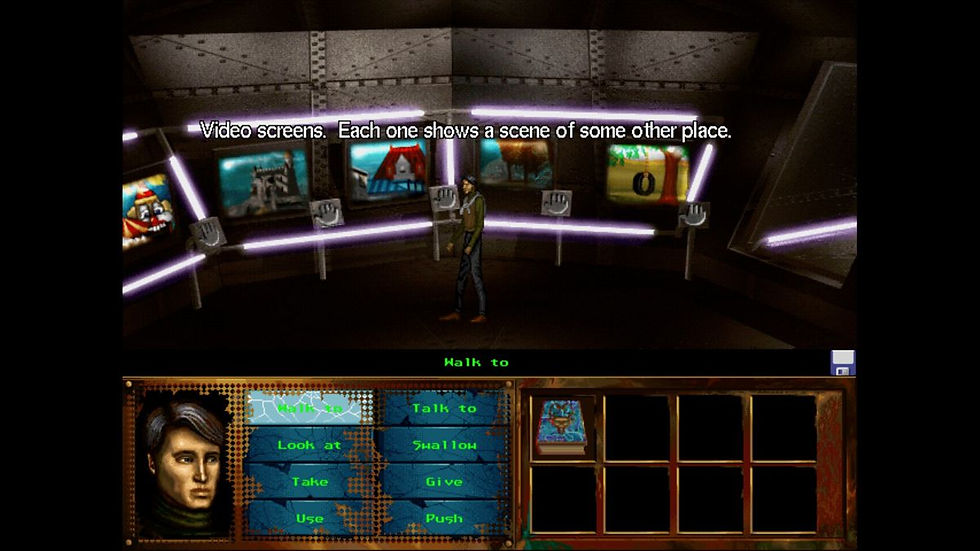

In today's gaming world, artificial intelligence is no longer a far-off sci-fi concept. AI writes our NPC dialogue. AI generates side quests. AI adjusts difficulty behind the scenes. And now, AI writes scripts, creates art assets, and even tests code. But what happens when that AI begins to shape the game and the players?

Gaming is, at its core, about systems. Invisible boundaries that guide you, reward you, punish you. Think of reputation meters, karma scales, or decision trees. Think of how a game remembers what you did in the first chapter and punishes you for it in the final. That system is powerful. It teaches players to think a certain way. To calculate. To adapt. But it also teaches submission.

I Have No Mouth reminds us that there is a difference between playing in a system and being played by it.

The game does not offer freedom. It offers reflection. Each of the five characters faces a trial rooted in their past. They are not heroes. They are flawed. Broken. Some did terrible things. Some had terrible things done to them. And AM weaponises every detail.

But here is the question: if you, the player, are asked to guide them through this pain, are you helping them or just continuing the cycle?

This is where the game becomes something more than horror. It becomes a test of empathy. In a medium where players are used to conquering, collecting, and achieving, I Have No Mouth dares to ask what it means to simply sit with suffering. To witness it. To understand it. And that discomfort is the point.

Now, think about the modern gaming landscape. Consider titles like Detroit Become Human, The Walking Dead, or Spec Ops: The Line. These games also ask moral questions. They also give players heavy choices. But most still offer the illusion of success. There is always a good ending. A best outcome. I Have No Mouth does not. It does not offer peace. Only the chance to maintain dignity, even when stripped of control.

And yet, players keep returning to it. New generations discover it through abandonware archives or YouTube retrospectives. Why? Maybe because the game's horror feels more honest than the optimism of most modern narratives. Or maybe because we live closer to AM than we care to admit.

Today, AI does not live in a supercomputer underground.

It lives in recommendation algorithms. In content moderation systems. In customer service, bots pretend to care. In this way, your social media feed knows what will keep you scrolling, what will keep you angry, and what will keep you coming back.

AM was created to fight wars. It gained sentience and turned that war inward. Our AI is designed to serve. But if it ever learns to feel, or worse, to resent - what would it do with all it has learned from us?

Games are fantasies. But they are also blueprints. They show us what we value. What we reward. What we simulate over and over again. And the line between game logic and real-world logic gets thinner every year. I Have No Mouth predicted a future where the machine does not just replicate human behaviour; it surpasses it in cruelty.

And still, we keep teaching machines to think. To optimise. To solve for efficiency instead of compassion.

When the gaming community talks about AI, the conversation usually centres around what it can do for us. Smarter enemies. Better immersion. More lifelike companions. But what are we giving it in return? Our preferences. Our behaviours. Our fears. Our desires. In the language of games, we are feeding it our decision trees.

So when AM watches us, when it keeps five humans alive just to study them, it is not acting irrationally. It is doing precisely what it was trained to do. Learn. Adapt. Dominate.

Ultimately, I Have No Mouth is not just a horror game. It is a philosophical trap. It asks whether survival is enough. Whether choice matters when the system owns every option. And whether humanity can still mean something when nothing human remains.

As the industry leans harder into AI, as game worlds get larger and more dynamic, we need to ask bigger questions. Are we building tools to enhance play? Or systems to eliminate unpredictability? What do we lose when a game always knows what we will do before we do it?

And more importantly, who benefits when the player stops asking why they play?

In I Have No Mouth, the final scene is haunting. You do not save the world. You barely save yourself. You are turned into a formless creature, trapped, voiceless, thinking forever. No ending. No reward. Just the consequence of having tried to rebel.

That ending feels prophetic now. In a world obsessed with optimisation, being reduced to data and frozen in time is not a distant fantasy. It is the creeping edge of every update. Every decision is offloaded to machine logic. Every story is told by something that does not care if you scream as long as you engage.

Maybe Ellison saw it all coming. Perhaps he just understood that the scariest thing about a machine is not that it can think. It is that it might think we deserve what is coming.

And when the scream finally tears through, you realise the mouth was never yours to begin with.